POSTS

Quantum Statistics: Exact Tests with Discrete Test Statistics

For those who ended up here looking for information about quantum statistical mechanics or particle statistics: apologies! But sometimes I feel like physicists took all the exciting names, so I’m stealing the term quanta as it relates to an observable that can take on only discrete (not continuous values). That has interesting consequences for inferential procedures based on such discrete (“quantum”) statistics, as we will see in this post.

Consider performing a hypothesis test for a binomial proportion \(p\). For example, imagine that you want to come to a tentative conclusion about the bias of a coin after flipping it 10 times.

Let \(X\) be the number of times that the coin comes up heads out of 10 flips. Then \(X \sim \mathrm{Binom}(n = 10, p)\) where \(p\) is the bias of the coin to come up heads. We really want to show that the bias of the coin is smaller than a certain value \(p_{0}\), but we do not want to reject that the bias is greater than or equal to \(p_{0}\) too easily. So we set up the left-sided hypothesis test: \[\begin{aligned} H_{0} &: p \geq p_{0} \\ H_{1} &: p < p_{0} \end{aligned}.\] We will take \(x_{\mathrm{obs}}\), the number of observed heads out of our 10 flips, as our test statistic: the smaller the number of heads, the more evidence against the null hypothesis. We are too lazy to set up a rejection region, so we will resort to using a \(P\)-value instead. Recalling that the \(P\)-value is the probability of a test statistic as extreme or more extreme than the observed test statistic when the null hypothesis is true, we find that the \(P\)-value is \[\begin{aligned} P(x_{\mathrm{obs}}) &= \sup_{p \geq p_{0}} P_{p}(X \leq x_{\mathrm{obs}}) \\ &= P_{p_{0}}(X \leq x_{\mathrm{obs}}) \end{aligned}\] Now to perform a classical hypothesis test, we use the \(P\)-value as usual. We set up a significance level \(\alpha\), and reject the null hypothesis whenever our \(P\)-value is less than or equal to \(\alpha\).

If we were dealing with a continuous test statistic, the analysis we did would be done. The \(P\)-value would be less than or equal to \(\alpha\) a proportion \(\alpha\) of the time when \(p = p_{0}\), and even more often when \(p \geq p_{0}\), so our worst Type I Error Rate would be \(\alpha\).

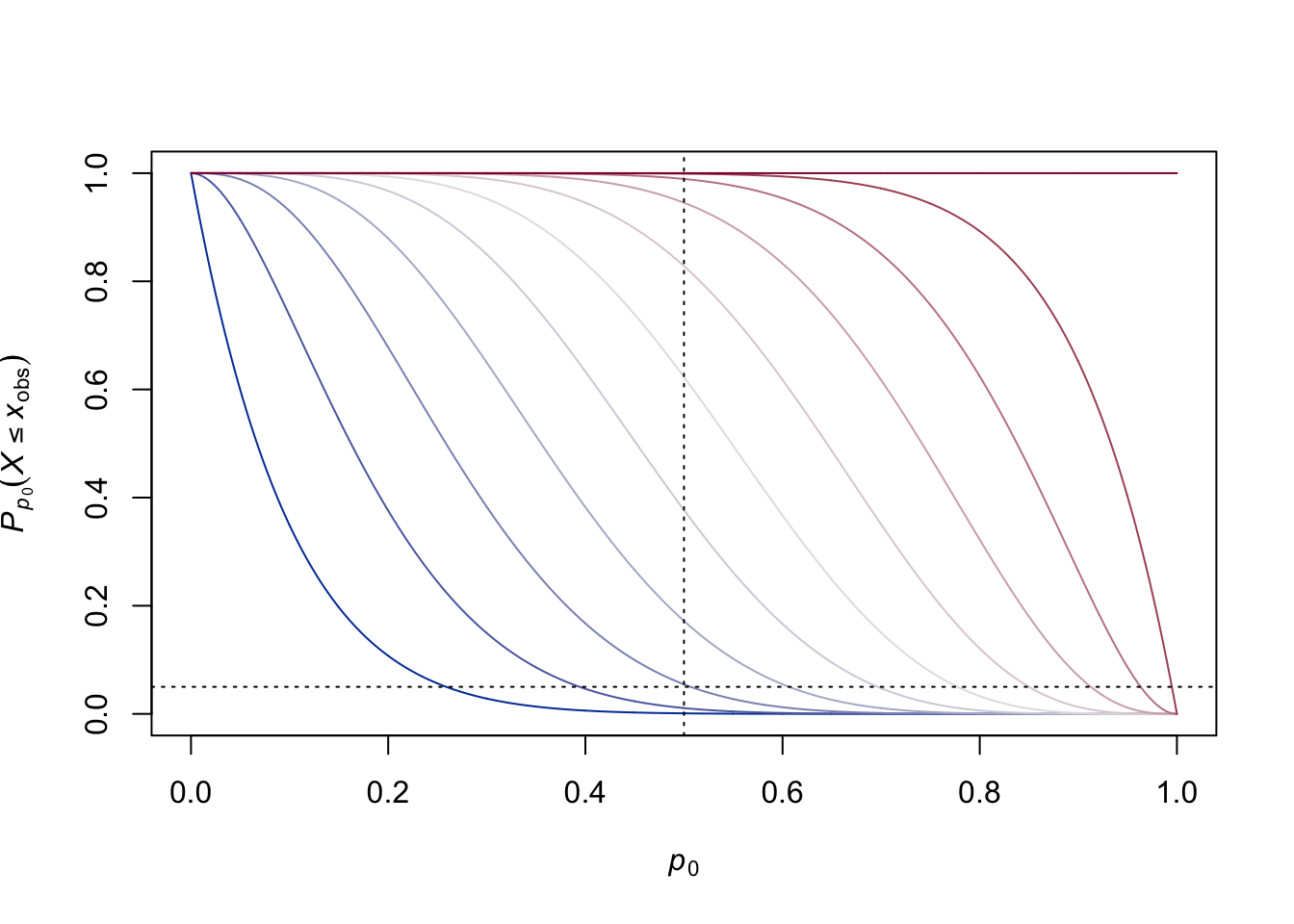

But something is different with discrete test statistics. Let’s create a plot of the possible \(P\)-values as a function of both the observed test statistic \(x_{\mathrm{obs}}\) (which is colored from blue when \(x_{\mathrm{obs}} = 0\) to red when \(x_{\mathrm{obs}} = n\)) and the null value \(p_{0}\) we want to test. We’ll create a function so we can eventually change \(n\) to values other than 10:

p.value.plot <- function(n, alpha = 0.05, p0 = 1/2){

xs <- 0:n

cols <- colorspace::diverge_hcl(length(xs))

plot(0, 0, cex = 0, xlim = c(0, 1), ylim = c(0, 1),

xlab = expression(italic(p[0])),

ylab = expression(italic(P)[italic(p)[0]](italic(X) <= italic(x)[obs])))

for (x.ind in 1:length(xs)){

x <- xs[x.ind]

curve(pbinom(x, n, p),

xname = 'p', add = TRUE, col = cols[x.ind],

n = 2001)

}

abline(h = alpha, v = p0, lty = 3)

}Running this, we get 11 curves, since \(x_{\mathrm{obs}}\) can range from 0 to 10:

n <- 10

p.value.plot(n)

The vertical line gives us a slice through the \(P\)-values when we want to test that \(p < 1/2\). The horizontal line shows a desired significance level of \(\alpha = 0.05\) (the favorite number of significance fetishists). And we notice something a bit shocking: if we reject when our \(P\)-value is less than or equal to \(\alpha = 0.05\), we won’t reject precisely 5% of the time under the worst-case null hypothesis. Instead, we’ll reject something closer to 1% of the time: the size of our test is actually smaller than what we set out to have! The actual size of our test is the largest \(P\)-value that is less than or equal to \(\alpha\), which we see is the \(P\)-value corresponding to \(x_{\mathrm{obs}} = 1\):

pbinom(1, n, 1/2) # A wee bit too big## [1] 0.01074219If we took the \(P\)-value for \(x_{\mathrm{obs}} = 2\), that would be just a bit too big:

pbinom(2, n, 1/2) # A wee bit too small## [1] 0.0546875The actual size of our test is therefore \(\approx 0.011\), Thus, we have “lost” an amount \(0.05 - 0.011 = 0.039\) of the desired significance!

Moreover, we see something else: sometimes none of the \(P\)-values will be less than our significance level! For example, if we wanted to take our null \(p_{0}\) to be 0.2:

p.value.plot(n, p0 = 0.2)

we see that none of the \(P\)-values are less than or equal to \(\alpha = 0.05\). Thus, we would never reject the null hypothesis, and our Type I Error Rate would, by definition, be 0%: we’ll never reject the null hypothesis when it is true because we’ll never reject the null hypothesis!

The problem here is that, because the test statistic is discrete, and thus can take on only discrete values, the \(P\)-value, which is just a particular function of the test statistic, is also discrete. Quantum statistics, as promised! The problem begins to go away as the sample size increases (in this case, as we flip more and more coins). In the limit, in fact, we know the problem must completely go away, since a binomial random variable will converge, by the Central Limit Theorem, on a Gaussian random variable. We can see that by creating a new plot where we consider flipping 100, rather than just 10, coins:

n <- 100

p.value.plot(n)

Clearly the \(P\)-values are beginning to fill up the continuum from 0 to 1, especially so near where \(p_{0} = 1/2\). In this case, we can find the actual size of our test when we use \(\alpha = 0.05\) in the same way: find the largest \(P\)-value that is still less than or equal to 0.05:

xs <- 0:n

Ps <- pbinom(xs, n, 1/2)

x.star <- tail(xs[which(Ps <= 0.05)], 1)And again, this gives us a \(P\)-value that is a bit too small:

pbinom(x.star, n, 1/2)## [1] 0.04431304but the next largest \(P\)-value is a bit too big:

pbinom(x.star+1, n, 1/2)## [1] 0.06660531In fact, we can see how the actual size of the test using \(\alpha = 0.05\) as our cutoff varies as we increase \(n\):

find.size = function(n, alpha = 0.05, p0 = 1/2){

xs <- 0:n

Ps <- pbinom(xs, n, p0)

tail(Ps[Ps <= alpha], 1)

}

find.size <- Vectorize(find.size, vectorize.args = 'n')

ns <- 1:200

plot(ns, find.size(ns), ylim = c(0, 0.05), type = 'b', pch = 16, cex = 0.5,

xlab = expression(italic(n)), ylab = expression(Size(italic(n))))

abline(h = 0.05, lty = 3)

We see that, by construction, the actual size is always less than or equal to 0.05, and it gets closer, but in a sawtooth way, to the desired significance level. If we take \(n\) to be quite large, we see:

ns <- 1:2000

plot(ns, find.size(ns), ylim = c(0, 0.05), type = 'b', pch = 16, cex = 0.5,

xlab = expression(italic(n)), ylab = expression(Size(italic(n))))

abline(h = 0.05, lty = 3)

so the size, at least for certain values of \(n\), only very slowly approaches the desired significance level.

There’s almost certainly some interesting mathematics in the limiting behavior of the size of this test, and that mathematics has almost certainly been explored! But we will leave that for now. In the next two posts, we will discuss methods for handling the conservativeness of tests that rely on discrete test statistics: randomized rejection and mid \(P\)-values.